When T-Pain played his NPR Tiny Desk Concert in 2014, the write-up and the comments were, of course, about the studio effect he had cemented into popular consciousness – or rather, its absence. The performance proved the artist – whose breakout album Rappa Turnt Sanga popularized the much-maligned Auto-Tune – could indeed sing, a criticism that had long been levied for his perceived overuse of the effect. The stigma around Auto-Tune and the impact it had on T-Pain's career, however, tell us as much about what aesthetic – and even moral – anxieties we have about modern music-making as it does about the music being made.

Pioneered by Antares Audio Technologies in 1997, Auto-Tune takes a singer's vocal track and digitally adjusts the pitch until it is perfectly in tune. The exaggerated version of the effect, which hit mainstream radio waves just one year later with Cher's "Believe," happens when attack – or how long it takes for the pitch correction to kick in – is turned all the way up. It makes voices sound robotic, abruptly switching between notes rather than gliding between them. More subtle uses of Auto-Tune are nearly ubiquitous in pop music; it's likely that some of your favorite singers use it regularly, albeit subtly. In the early 2000s, seemingly everyone cranked up the effect on a track or two, but the shine eventually wore off. Artists like Neko Case and Jay-Z decried the over-use of the effect, calling for a return to more "honest" music-making. Any use of Auto-Tune became suspect – the hallmark of talentless, lazy cheaters. Antares' newest products work in real time at live performances, further compounding the issue.

The dramatic outcry against Auto-Tune misses the entire picture, however. Producers have many tools at their disposal to alter a vocal performance and frankly, it's their job to do that. There is no outcry about de-essers, but if they are dialed too high, all of the "s" sounds in a song turn into "th," giving the singer a lisp they didn't have when they went into the studio. When used more subtly, they can save an otherwise excellent take where the microphone picked up too many sibilants (the hissing sound an "s" makes). Similarly, engineers often use Auto-Tune to tighten up an already excellent performance rather than to fix a sloppy one, subtly correcting a note or two. Prior to Auto-Tune, singers might re-record (or "punch in") these notes, but this saves time and effort for the same result. In other words, fixes have always appeared in the mixes, and ultimately, studio tools are simply that – tools – which benefit some artists but aren't useful to others. What's to say one artist's approach is inherently better?

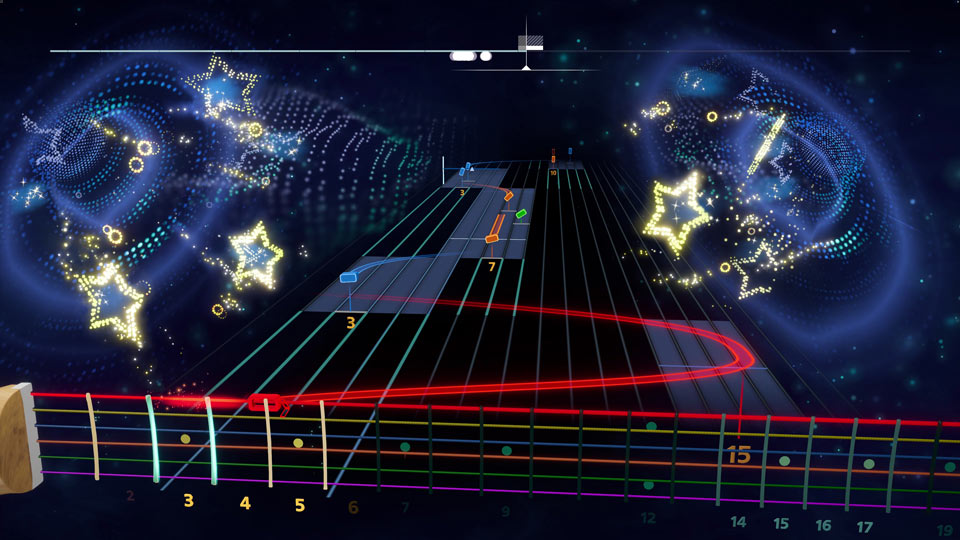

![[RS+] tpain _960.jpg](http://staticctf.ubisoft.com/J3yJr34U2pZ2Ieem48Dwy9uqj5PNUQTn/1o4iNVk0jCC46wyZgJCi4i/c773623675a2324aff273d37f5287c4f/tpain_960.jpg)

T-Pain's generous use of Auto-Tune created his signature sound – and a lot of controversy.

Enough philosophizing – back to T-Pain. Media coverage implies garish Auto-Tune overflows from all T-Pains tracks, but listen to the subtle dialing up and down of the effect on the first verse of "Blow Ya Mind." Auto-Tune may be consistently lurking in the background, but it only pops in for a syllable or two in the verses, making the effect more rhythmic than melodic, snapping words to the beat in a way that a human voice would struggle to do on its own. Over the course of the song, the effect becomes more prevalent at times, less at others. In other words, it's used thoughtfully and dramatically, a far cry from laziness.

As Leon Neyfah suggests in The New Yorker, perhaps the backlash to Auto-Tune was not so much in its moral stakes, but how much it proliferated after T-Pain first popularized it. The fault, it seems, is in its saturation rather than any kind of cutting corners. In any situation where there are many tools at your disposal, take the challenge to use them creatively and think outside the box. Just don't be surprised if you start a trend that ultimately runs awry.

Margaret Jones is a multi-instrumentalist, songwriter, and music teacher living in Oakland, CA. She plays guitar in several local bands including her own songwriting project M Jones and the Melee. She also holds a Ph.D. in Music History from UC Berkeley and has taught at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music.

T-Pain by Andrew J. Kurbiko is licensed under CC BY-2.0.

T-Pain I 2 by Will Folsom is licensed under CC BY-2.0.

Interested in more from this artist? Learn to play their music and more with Rocksmith+.